This article is featured in Bitcoin Magazine's "The Privacy Issue". Subscribe to receive your copy.

First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.

The quote—commonly misattributed to Mahatma Gandhi—has been overused to the point of exhaustion in the Bitcoin space, typically invoking the suggestion that the laughing stage is over. In most of these cases, the insinuation that the fighting stage has begun was overblown, however; perhaps inspired by little more than a comment from some politician or finance professional.

But on April 24 of this year, the quote finally rang true.

On that day, the US Department of Justice (DoJ), via the District Court of the Southern District of New York, announced the indictment of Samourai Wallet co-founders Keonne Rodriguez and William Hill. Rodriguez, Samourai Wallet’s CEO who pseudonymously operated the @SamouraiWallet handle on Twitter/X, was arrested early that morning in his home state of Pennsylvania. Hill (AKA TDev, or @SamouraiDev on Twitter), meanwhile, was arrested in Lisbon, Portugal, where he resided; at the time of writing this article, the DoJ intends to extradite him to the US.

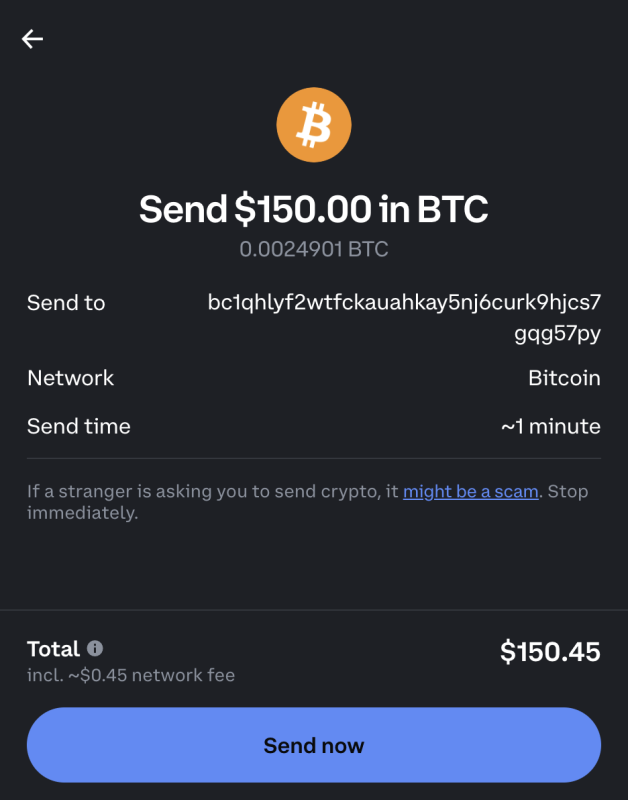

Both of them are accused of running an unlicensed money transmitter, and earning millions of dollars in fees doing so. For this, Rodriguez and Hill each face a maximum prison sentence of five years.

On top of that, the duo was charged with money laundering as well. According to the DoJ, Samourai Wallet was used to launder over $100 million dollars of crime proceeds from dark net markets, fraudulent schemes and other illicit activities. This could add a whopping maximum 20 years to their sentence.

Samourai Wallet’s web servers and domain (samourai.io) were also seized, rendering the wallet largely unusable. (Though users could still recover their bitcoin through other wallets, using their backup seeds.)

Around the same time as the Samourai Wallet developers’ arrests, the FBI issued a public warning to cryptocurrency users, stating that they may lose their funds due to criminal seizures if they don’t move their holdings to regulated entities. Although Samourai Wallet was not mentioned by the agency, the timing of the note suggests the warning was no coincidence.

Together, it seemed to represent a step change for Bitcoin and Bitcoin development.

Bitcoin Privacy

Bitcoin comes from a long tradition of privacy activism. In a world where money is increasingly going digital, Cypherpunks have since the 1990s attempted to create a form of electronic cash in order to prevent an Orwellian future where every transaction can be monitored and potentially censored. Similarly, Douglas Jackson around the turn of the millennium offered a gold-backed digital payment system with privacy features called eGold, which eventually had to shut down operations because Jackson did not register his company as a money transmitter.

eGold required a money transmitter license because it held gold in reserve on behalf of its users, but it has since then generally been assumed that creators of non-custodial wallet software did not qualify as money transmitters. As long as developers never took control of user funds themselves, they did not need to register with the United States Department of the Treasury's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), and therefore also wouldn’t need to apply anti-money laundering (AML) and Know Your Customer (KYC) checks on their users— or so it was thought.

Crucially, this assumption was in large part based on guidance from FinCEN itself, published in 2013.

By extension, many presumed that developers wouldn’t be held accountable for how their software is used. If non-custodial Bitcoin wallets are used to launder money, those engaged in the activity itself would be breaking the law, but it was generally not believed to be the responsibility of the creators of these wallets to prevent this from happening in the first place.

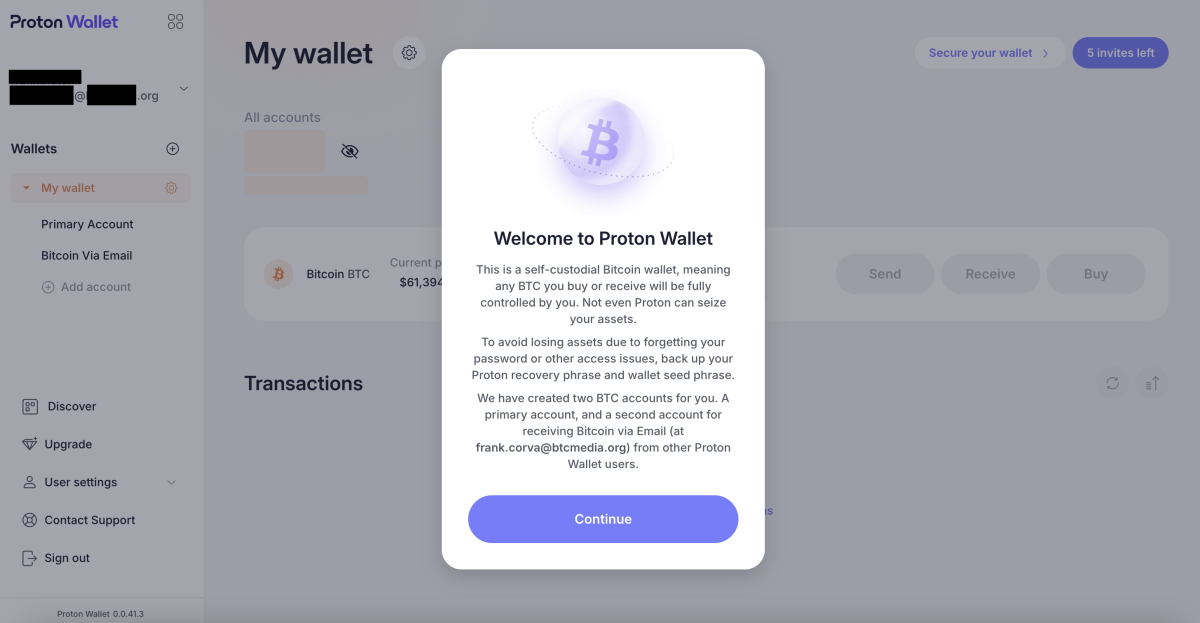

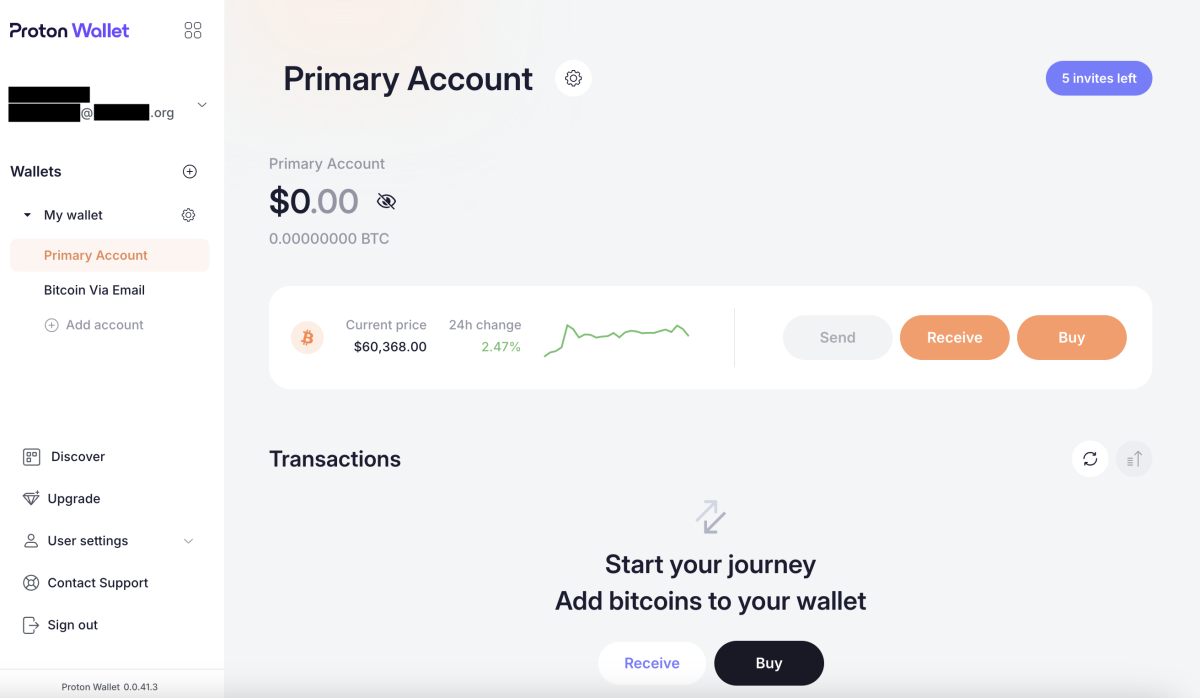

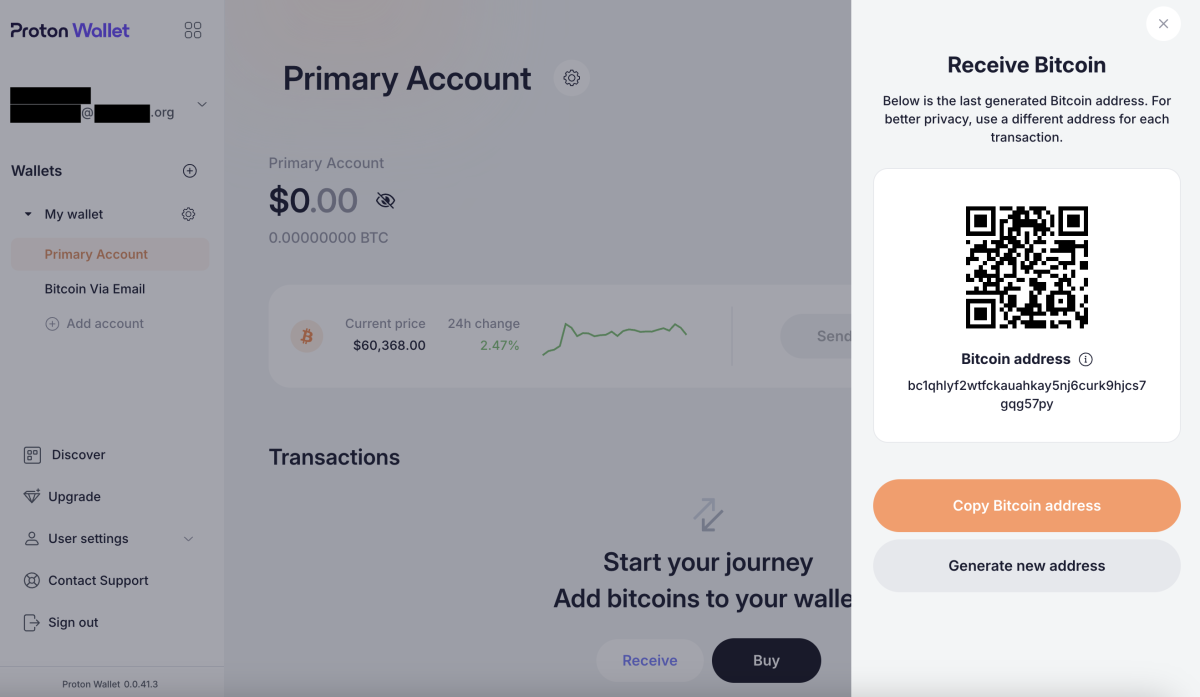

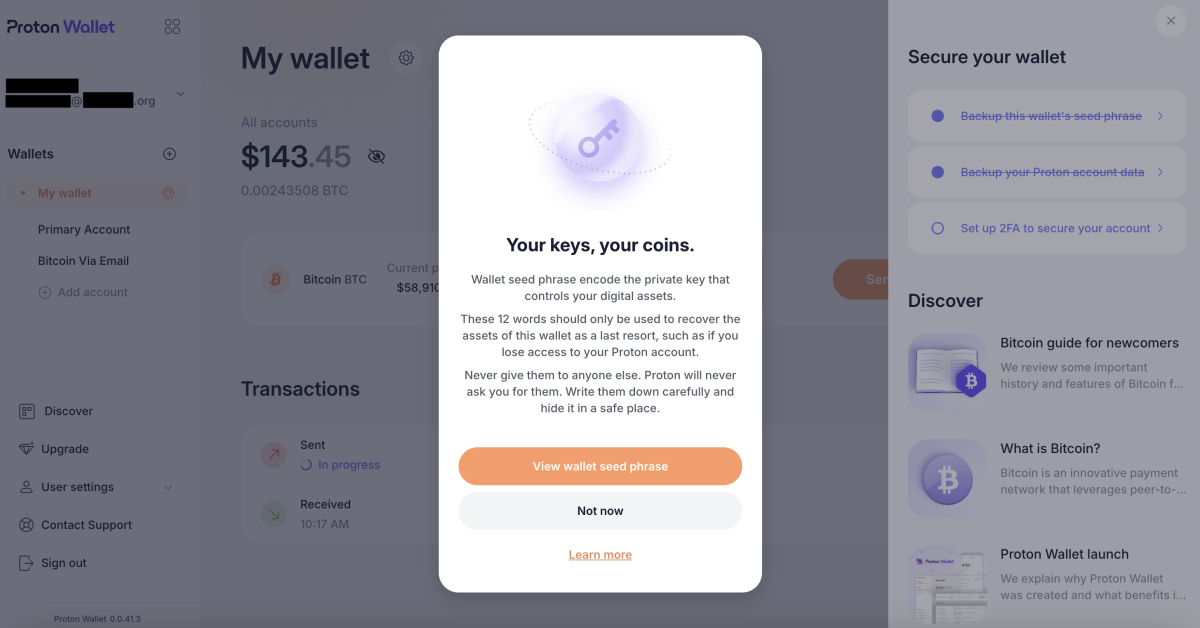

Samourai Wallet was, indeed, a non-custodial wallet. Users stored their own private keys in their wallet software, so Rodriguez or Hill at no point controlled these bitcoin. By default, the Samourai Wallet application did communicate with a central server to send and receive transactions, but even this could be sidestepped by connecting to the Samourai Dojo: a personal, internet-connected device that embedded a Bitcoin node.

Importantly, Samourai Wallet was marketed as a privacy wallet, and its main privacy feature—Whirlpool—did fully depend on the Samourai server. Specifically, Samourai Wallet users could, coordinated through this central server, collaborate to make CoinJoin transactions. In groups of five, users would contribute an equal amount of bitcoin (for example 0.01 BTC) to a transaction, which sent back the same amount to each of them.

Because there is no way to link specific transaction inputs to specific transaction outputs, this essentially “mixed” their coins. Blockchain analysts would be unable to trace back the history of these coins, except to the extent that they’d know they must have come from one of these five inputs. Furthermore, Whirlpool users could opt to automatically repeat such mixes, even further obfuscating their transaction history.

In addition, Samourai Wallet offered a service called Ricochet. This enabled users to send bitcoin to newly generated addresses they controlled themselves multiple times, somewhat frustrating blockchain analysis as well. (Although this is possible with any Bitcoin wallet, Samourai Wallet automated the process.)

The allegation, as put forth by the DoJ, is that these tools were, indeed, used to launder money. What’s more, the federal department argues that the Samourai Wallet co-founders intended this to be the case. This accusation is largely based on public as well as private communication about their service, including some statements by Rodriguez and Hill on Twitter and in their pitch decks intended for investors, which mentioned that individuals who engaged in “illicit activity” on “restricted” or “dark/grey” markets would be among their user base.

Whether these statements truly indicate that Rodriguez and Hill intended their software to be used for illicit purposes—as opposed to it just being “tough marketing talk” from developers who ultimately wanted to offer financial privacy tools—will have to be proven in court.

And perhaps more importantly, the Samourai Wallet arrests challenge the long-standing assumption that developers don’t have to register as money transmitters and perform the associated AML and KYC checks.

Though, this assumption had already been put to question in a different corner of the cryptocurrency space…

Tornado Cash

In August 2022, the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) added Tornado Cash, a smart contract on the Ethereum blockchain, to its OFAC list. It made interacting with the smart contract illegal under US law.

Later that same month, Alexey Pertsev was arrested by the Dutch police. In the years prior, Pertsev had, along with Roman Storm and Roman Semenov, founded and operated software development company PepperSec. Key to their efforts had been the development of Tornado Cash as well as supporting infrastructure.

As a smart contract, Tornado Cash technically functions autonomously. Although Pertsev helped develop the tool, it exists across thousands of Ethereum nodes around the world. After it was released, Pertsev had no way to control how it was used, or who used it. Anyone could send an amount of ETH to the smart contract, which—utilizing a cryptographic trick called zero-knowledge proofs—enabled them to withdraw that same amount from the smart contract, but to a different account. Here, too, there was no way to link the ETH going into Tornado Cash to the ETH going out, thus the smart contract essentially functioned as a “mixing” service.

To make this feature effective, PepperSec also developed supporting infrastructure, which in part relied on relayers: basically, Ethereum users could be tasked with paying the Tornado Cash fee, for which they in turn were rewarded TORN tokens. This aspect of the design—the relayers and the TORN tokens—centered around a different smart contract on the Ethereum blockchain, which technically was implemented as a decentralized autonomous organization (DAO).

In addition to that, PepperSec operated a service that offered an easily accessible graphical user interface (GUI) for the smart contract and its surrounding infrastructure.

Importantly, Tornado Cash as well as the supporting infrastructure was all non-custodial software. Pertsev, Storm and Semenov developed code, but they at no point controlled any of the ETH going into the smart contract. Although they couldn’t control how Tornado Cash could be used, it’s less obvious to what extent the same was true for the supporting infrastructure. (Like many things Ethereum, claims of “decentralization” were at least in part grounded in marketing more so than in technical reality.)

In either case, for the Dutch prosecutor, the fact that Pertsev and his colleagues never took custody of any ETH did not make much of a difference. In her view, PepperSec was de facto ran as a business, which—albeit indirectly through the TORN token—earned an income from Tornado Cash and the supporting infrastructure. She argued this made Pertsev responsible for how Tornado Cash was used, and by whom.

In particular, she pointed out, Tornado Cash had been used to launder well over a billion US dollars, for example by North Korean state-funded hackers known as the Lazarus Group. Pertsev knowingly facilitated this kind of activity through the software he developed, she argued, and did nothing to prevent it. He had to be held accountable.

And as it would soon turn out, it wasn’t just the Dutch prosecutor who held this belief. About a year after Pertsev’s arrest in the Netherlands, his PepperSec co-founders Storm and Semenov were indicted in the United States, with the former (who resided in the US) arrested. (Semenov does not live in the United States; at the time of writing this article his whereabouts are unknown, but he is likely in a country without an extradition treaty with the US.)

Much like Pertsev, both of them are charged with money laundering, as well as running an unlicensed money transmitter business and sanctions violations. Storm will stand trial in New York this September.

Chilling Effect

The various arrests quickly appeared to have a chilling effect on other Bitcoin developers.

Even before Pertsev’s arrest, Bitcoin privacy wallet Wasabi Wallet—Samourai Wallet’s main competitor—in March of 2022 decided to implement AML checks in their mixing software, and reject coins that were suspected to have been used for illicit activity. (Although Wasabi Wallet, like Tornado Cash and Samourai Wallet, was fully non-custodial, the company behind the wallet—zkSNACKs—coordinated CoinJoin mixes through a central server.)

This new policy was harshly criticized by—among others—the Samourai Wallet team and other privacy focused bitcoiners. Rodriguez and Hill loudly and proudly proclaimed that their mixing service was open for business to anyone, and on social media adopted a much more adversarial attitude towards regulators and their KYC/AML regime. Indeed, it was exactly this attitude that may have gotten them in legal trouble.

More recently, the Samourai Wallet arrests moved other Bitcoin developers to take additional precautions as well. Just one day after the indictment, Sparrow Wallet, which had been compatible with Samourai Wallet’s Whirlpool, for example released a new version of its software that disabled this feature. Shortly after, development company ACINQ announced that its Phoenix Wallet (a Lightning wallet) would be removed from US app stores, citing on Twitter that “[r]ecent announcements from US authorities cast a doubt on whether self-custodial wallet providers, Lightning service providers, or even Lightning nodes could be considered Money Services Businesses and be regulated as such.”

And in what was arguably the biggest setback for privacy in Bitcoin’s short history, Wasabi Wallet soon after announced to discontinue its mixing service altogether. With Whirlpool already down, the other major CoinJoin coordinator would seize operations per June 1st of this year.

The First Verdict

Just weeks after the Samourai Wallet developers’ arrest and the events that unfolded immediately after, on May 14th of this year, it was time for Pertsev’s sentencing.

In the courthouse of ’s Hertogenbosch, a small city about an hour south of Amsterdam, the Tornado Cash developer received the bad news. The panel of judges essentially agreed with the prosecutor on all counts, and in some ways went even further than the prosecutor was willing to go. The judges ruled that Pertsev was fully responsible for how the smart contract was used; the fact that some of the code that PepperSec produced was “unstoppable”, was not considered a valid excuse.

“Tornado Cash functions in the way the defendant and its co-founders developed Tornado Cash,” they stated. “So the operation is completely their responsibility.”

Pertsev was sentenced to 64 months in Dutch prison— though he did file for appeal, which at the time of writing is pending.

The next Tornado Cash court case will take place in New York, where Pertsev’s PepperSec co-founder Storm will stand trial. While the Dutch verdict should technically not affect the outcome of the American proceedings, the case and sentencing in the Netherlands might offer an indication of what can be expected: the Dutch prosecutors shared many of their files with their American colleagues.

Meanwhile, the first hearing for Samourai Wallet’s Rodriguez took place in New York last May as well. He will be awaiting the full trial on home arrest in Pennsylvania.

Still, despite these significant setbacks for Bitcoin privacy, the prospects of bitcoin mixing are not altogether dead. Most obviously, all American trials are yet to take place. (And even if Rodriguez, Hill and/or Storm are found guilty, they, too, can appeal to higher courts.) Meanwhile, JoinMarket—a tool that lets users create CoinJoin transactions without a central coordinator—continues operations uninterrupted. And while Wasabi Wallet has taken its central coordinator offline, the wallet itself will still be maintained.

What’s more, alternative Wasabi Wallet coordinators have already started offering their services: while not operated by zkSNACKs, this enables users of the wallet to create CoinJoin transactions between them in much the same way. Because such coordinators can even be operated anonymously over Tor, future prosecution of such services may be even harder as well— regardless of the outcome of the upcoming trials.

The fighting stage, indeed, has begun— and the fight is far from over. Whether the adage will ring true, and the winning stage follows next, remains to be seen.

via bitcoinmagazine.com